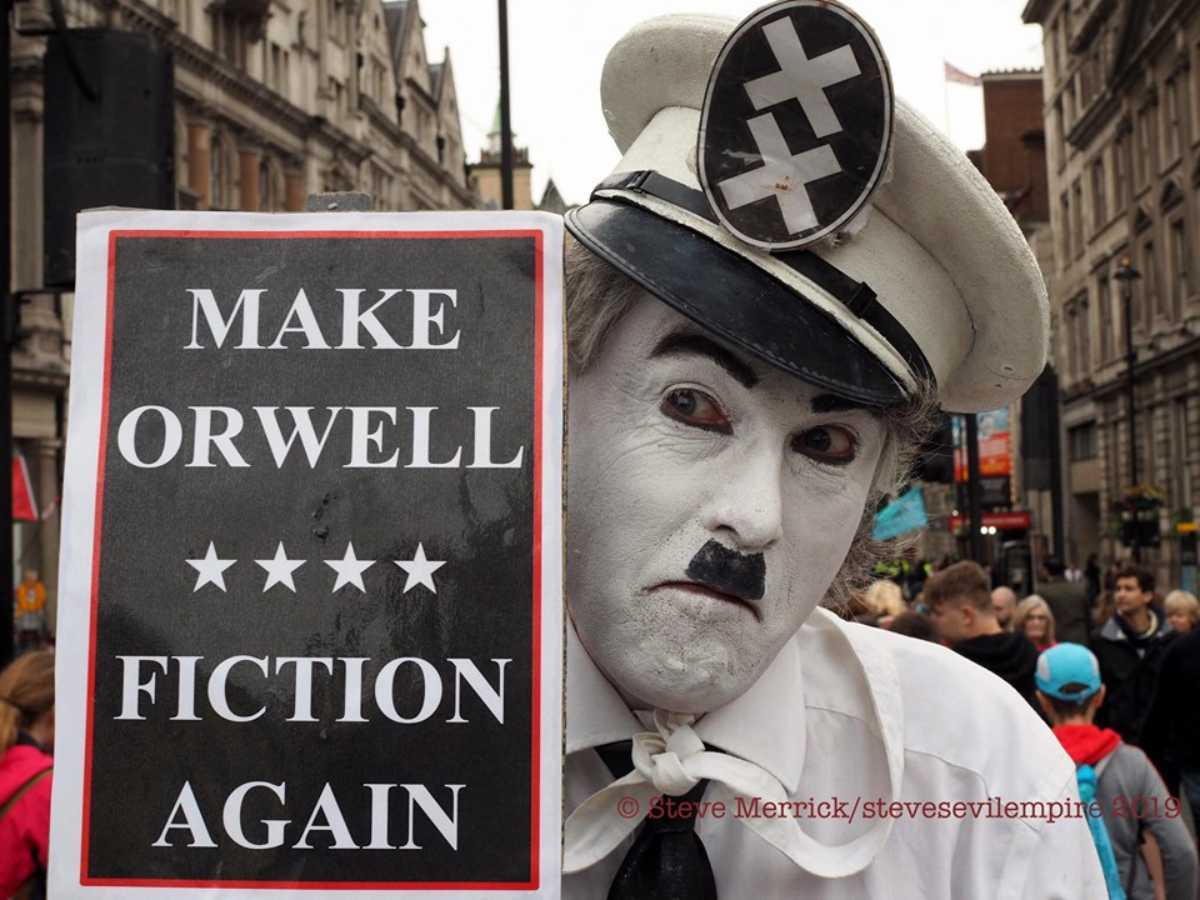

In 2006, I started to embody a new, difficult and edgy character – Adenoid Hynkel, the Great Dictator, Chaplin’s spirited and timely parody of Hitler. Finding myself trawling all the charity shops in the area looking for something that would pass as a jacket, I knew what I had wanted. It had to be white and stylishly cut, with silver buttons and breast pockets; perhaps a safari suit. This had pretty much narrowed my search down to the power suits in the lady’s section.

Charity shop fingerings

“That’s a woman’s jacket!” the shop assistant had barked at me, eyeing me up and down as I fingered a delicate crisp cream number with a plunging neckline.

“I know”, I had answered – innocently groping a generous 80’s style shoulder pad. “I’ll take it.”

That had been the final piece of the jigsaw. I had the shirt and a clip-on black tie, white tracksuit bottoms for the trousers, and thick black woolen socks pulled up for the jackboots. My mate had knocked me up an armband carrying the insignia of Hynkel’s Double Cross party, and I’d nicked an Essex policeman’s cap and painted it white:

I’d once gone to a party dressed as the Chaplin’s Little Tramp and been accosted by a drunken fool on the dance floor who’d kept giving me fascist salutes. But wearing that outfit, with white face paint and toothbrush tash, there could be no mistake.

That first dress rehearsal, I had put on the Sex Pistols (Holidays in the Sun) full blast, picked up my placard which had said ‘Free Sprachen Stunk’ (a quote from one of Hynkel’s speeches), puffed my chest out, and began marching round my front room saluting the pot plants. Then I had sat down to watch The Great Dictator on DVD.

Hitler, Chaplin, and The Great Dictator

For those who haven’t seen it, it is basically a tale of mistaken identity, where a Jewish barber from the ghetto called Schultz (Chaplin), a dead ringer for the tyrant Hynkel (also Chaplin), ends up getting the chance to deliver a message of peace and humanity to the world.

Hitler had apparently sat down to watch the movie on at least two occasions at his Bavarian mountain retreat. Even though the Nazis had hated Chaplin’s euphoric reception during his visit to Germany in 1931, one can only assume that Hitler had got some kind of perverse kick out of seeing this international superstar lampooning him. History did not record his reaction to the movie, but Chaplin apparently said that he’d “give anything to know what [Hitler] thought of it”.

Chaplin and Hitler were not only born the same week of the same month, but also the same year (1889). Both had difficult childhoods, with violent or alcoholic fathers and sick mothers. Both sought their fortunes in a foreign land. Chaplin played a tramp throughout his movie career, and Hitler had found himself living the life of a tramp on the streets of Vienna.

Legend has it that Hitler actually fashioned his ‘facial furniture’ on the Chaplin look, reducing the ‘walrus’ moustache that he had sported whilst serving as a lance corporal in the Bavarian army during the Great War, and gone for something a touch more modern and expressive.

Whatever the reasons behind the new look, I find it hard to believe that on the day that Adolf first ventured out without his fur handlebars, someone in the street didn’t point to him and laugh, “Got en Hemel! Das es Charlie Chaplin?”

‘Charlie’s done it better’

Crucially though, where the two men seem to part company is at the dawn of talking pictures, which seemed to mark the end of Chaplin’s ascendancy, and the rise of Hitler’s popularity. The Talkies loved passion, and Hitler did ‘passion’ brilliantly, greatly bolstered by unlimited budgets, innovations in camerawork and montage techniques, actual awe-inspiring locations, and a cast of adoring thousands. As spirited and successful as it was, Chaplin’s The Great Dictator, released in 1940 (but originated in 1938), could never match the propagandist punch of Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will, released in 1935.

Perhaps the last word on their relationship should go to the English comedian Tommy Handley, famous for the wartime radio programme ITMA (“It’s That Man Again“). Three days after Britain entered the war in September 1939, before the disaster at Dunkirk had truly kicked Britain awake, Handley took part in a BBC radio show called, ‘Who is that man who looks like Charlie Chaplin?’, during which he sang a song by the same title. It went like this:

“Who is this man who looks like Charlie Chaplin?

What makes him think that he can win a war?

It can’t be the moustache. That only makes us laugh!

And Charlie’s done it better, and before.

If it wasn’t for the boots and cane and trousers,

You couldn’t tell the 2 of them apart.

But the whole idea’s absurd. Charlie’s never said a word!

And Adolf couldn’t play a silent part!”

By the time he wrote his autobiography in 1964, with the immense gravity of hindsight, Chaplin had clearly grown embarrassed about the film’s slapstick nature, and he confessed that, had he known of “the actual horrors of the German concentration camps, I could not have made The Great Dictator: I could not have made fun of the homicidal insanity of the Nazis”.

My great dictator’s first outing

I chose the State Opening of Parliament for my first outing.

Wow! I’d never seen so many gunmen in all my life. There was bearskin and bullied boots from Parliament Square to Buck Palace, with hundreds of cops thrown in. And I was there to launch a leadership challenge, as the Queen’s golden bullet proof carriage rolled by.

I was instantly set upon by the police when I tried a silly flappy-armed salute that I had lifted from the film. A policeman came up to me and said:

I am aware of the films of Charlie Chaplin from the 1940s. But someone else might not be. If I see you making that arm gesture again, I will arrest you for breach of the peace.

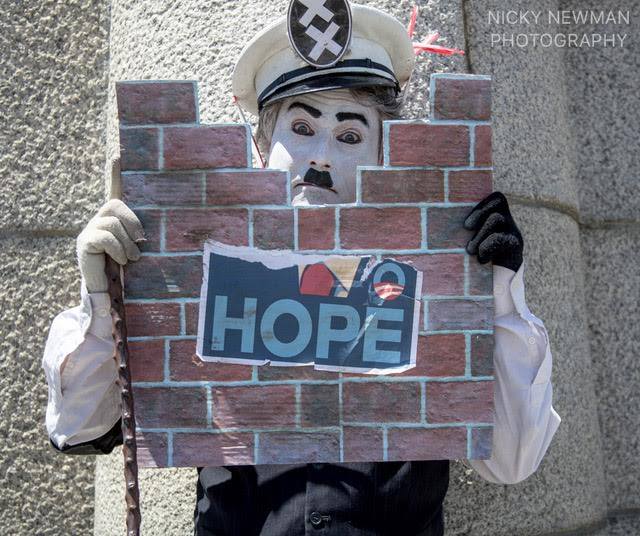

It was the day I got the veteran peace campaigner Brian Haw to read out the speech. And I remember thinking at the time, I’ve really got to learn this. Which didn’t happen for another 11 years.

During that time, I very rarely dressed up as the Great Dictator, perhaps half a dozen times. A protest on the day of Trump’s inauguration outside the old American embassy. Alongside the Trump baby blimp in Parliament Square during his state visit.

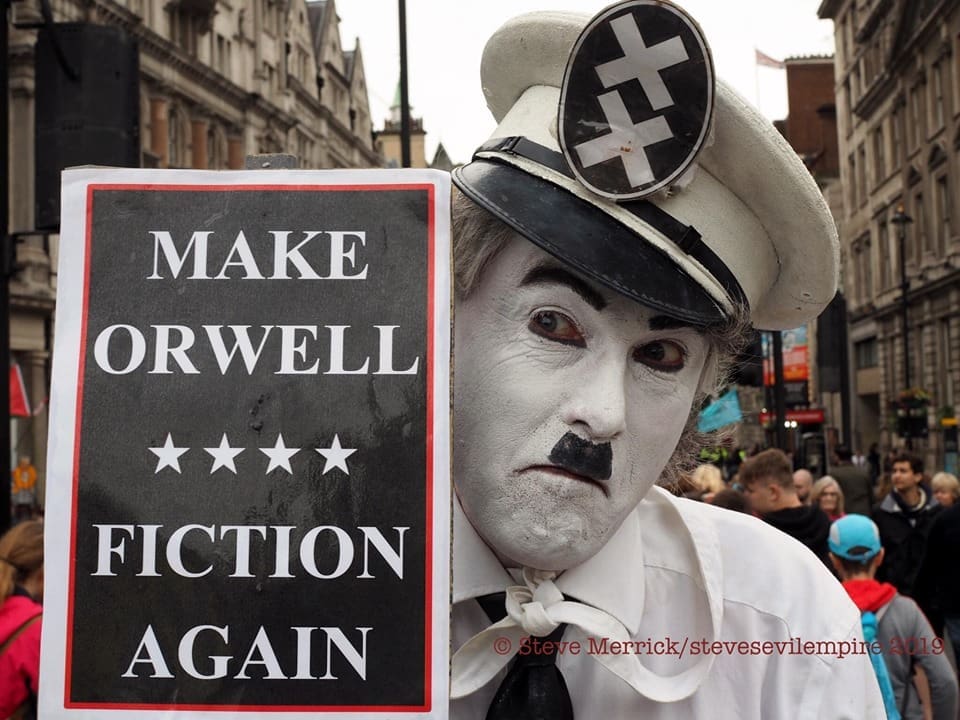

Outside an arms trade trial at Stratford Magistrate’s Court, holding a placard that said, ‘Greed has poisoned man’s soul’ – a line from the speech. At an anarchist bookfair in Cape Town. Once outside Downing Street, after Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, wearing a black hard hat with a nuclear explosion coming out the side, holding a sign that said, ‘Grab ‘em by the oligarchs’.

In truth, I’ve always felt uneasy doing the character, much preferring the playfulness and everybody’s friendliness of the Little Tramp. Dressed as Hitler means you are more likely to get challenged on the street. Which has happened a few times. Notably, when a Jewish man came up to me.

The fine line between comedy and tragedy

OK, full disclosure.

A man had just walked past and given me a Nazi salute. He was laughing and joking. And I, very stupidly, gave him a Nazi salute back. And this man had seen it, and quite rightly, wanted to know why I was making fun of the Holocaust. I fumbled around for some lame excuse, but there was really nothing I could say.

The Holocaust is no laughing matter. Full stop. And I vowed, if I was to ever dress up as the Great Dictator again, I would just stick to the speech, which really needs to be heard, nailing quite a few unassailable truths. Snippets of which have ended up in hundreds of memes, in graffiti, on t-shirts, even as tattoos, incorporating timeless sentiment and universal truth. Touching so many lives.

Like the policeman I met once at the station after one of my arrests, keeping watch as I used the loo, telling me he’d learnt it for his best mate’s wedding. Then the guy actually starts reciting whole chunks of it, while I’m sitting on the toilet. It was quite surreal.

More recently, three days before the election, me and the Dictator travelled up to Westminster to film the Double Cross Party election broadcast, very much with Labour in mind. What with their centrist policies and cosying up to the corporate media, Israel and the arms trade, their purging of any shred of socialism from a socialist party. Starmer betraying every leadership election pledge.

Labour has Double Cross written all over it.

Always armed with a large thought bubble that has ‘Free Speech’ written on it. For which I was once arrested, inside Tony Blair’s one-mile protest exclusion zone. You could say, Britain’s first thought crime. Also, very much aware of my Article 10 rights, to Freedom of Expression, about the only defence we have left. I have always seen the freedom to recite that speech, very loudly, right outside Downing Street, as my own personal litmus test as to how authoritarian our society is becoming.

Chaplin’s message of peace might get me arrested for breach of the peace. I might just get ignored. As I mostly have been. Lots of confused tourists, waiting for me to ‘do the box’:

We’ll see.

There’s a strong risk however that the centrist policies of the Double Cross Party will fall well short of the bold steps desperately needed to fix decades of austerity, social decline, and neo-liberal looting, and that this would only serve to empower those tyrants waiting in the wings with beautiful words on their lips, always ready to steer resentment and blame far right. And I’ll be there too, for as long as I can be, with Chaplin’s beautiful words on my lips, crying out, ‘People, don’t give yourselves to brutes!’

Featured image and additional images via Neil Goodwin