The following investigation is by Monica Piccinini, Lucas Ferrante, and Philip Fearnside, and was originally published on 9 September, in Portuguese, on Amazonia Real

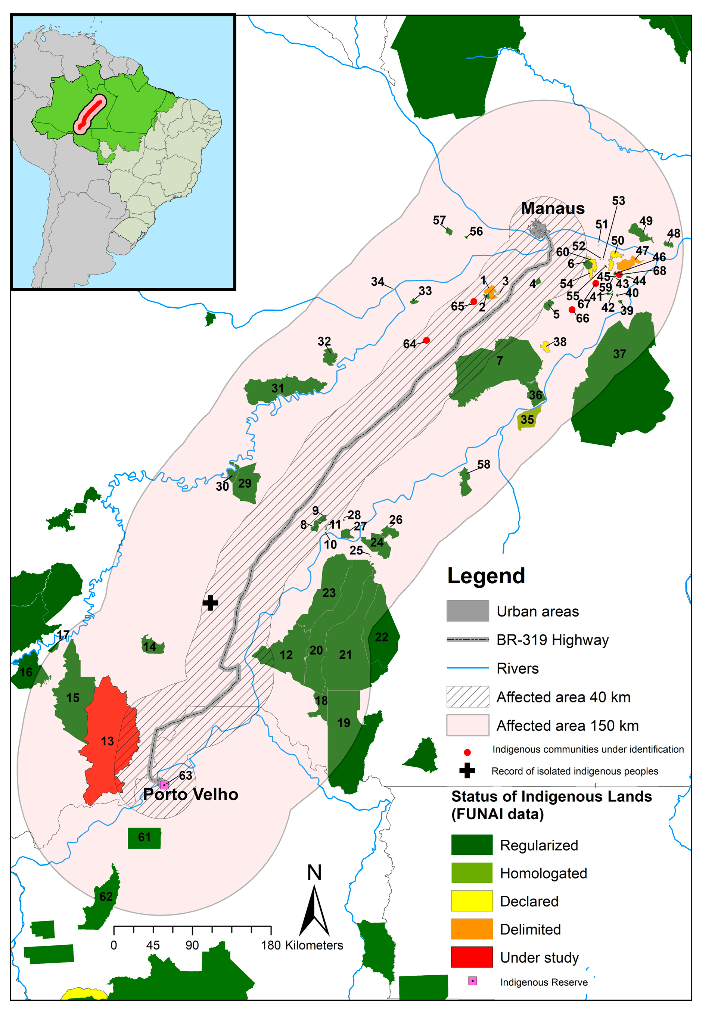

Brazil’s Ministry of Transportation plans to “reconstruct” a 406km stretch of the Amazon BR-319 highway, connecting Manaus, the capital of the state of Amazonas, to Porto Velho, on the southern edge of the forest. The road, abandoned in 1988, has seen gradual improvements since 2015 through a “maintenance” program:

The BR-319 project in Brazil’s Amazon

Currently, the BR-319 highway is passable during the dry season, although the environmental license needed for the reconstruction project to create a new highway along the same route has not yet been granted.

The reconstruction of the BR-319 highway would connect the relatively intact central Amazon to the notorious deforestation hotspot known as “AMACRO”, a name composed of the acronyms for the states of Amazonas, Acre, and Rondônia.

The BR-319 route passes through one of the most preserved blocks of the Amazon rainforest, and the proposed roads linking to BR-319 would open to the vast forest area to the west of the Purus River that parallels BR-319.

BR-319 would also allow deforesters from Brazil’s “arc of deforestation” in the southern Amazon to migrate to Roraima, which borders Venezuela in the northern Amazon, as well as to other areas already connected to Manaus by road.

Overall, half of what remains of Brazil’s Amazon forest would be impacted, not just the roadside of the BR-319 itself, which is the focus of the licensing process and the efforts of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to mitigate impacts. Several studies provide extensive information on the project’s impacts and the reasons it should be halted.

NGO power and influence

A key factor pushing towards the environmental and social disaster that the BR-319 project comes from an unexpected sector: several environmental NGOs and the foundations that support them. Although it’s difficult to picture an environmental organisation not opposing the BR-319 project, some do.

The Observatory of Climate, which is composed of 120 Brazilian NGOs, has taken a strong stance against the BR-319 project and brought a public civil lawsuit (ACP) against the federal environmental authorities for having granted a “preliminary license” for the project.

The lawsuit was judged favourably on 25 July 2024, suspending the preliminary license that had been granted during the 2019-2022 presidential administration of Jair Bolsonaro, which had passed over the negative technical opinions of the licensing staff to accommodate political pressures. The preliminary license does not authorise road construction, but it allows significant preparations to obtain an “installation license” that would allow road construction to begin.

NGOs that have refused to condemn the BR-319 project have taken the position that the road’s environmental approval and execution are inevitable, leading them to adopt a neutral stance on whether it should be built, and instead focus on governance strategies for when the road is completed. The road’s construction is not fait accompli and assuming that the project is inevitable, contributes to making it a self-fulfilling prophecy.

These NGOs believe that the project should go ahead provided all requirements for environmental licensing are met, including consultation with impacted Indigenous peoples. This became apparent on 5 February 2020, when the Federal Public Ministry in Manaus held an event to discuss the BR-319 project’s impacts. The third author of this text gave a presentation explaining why the road project should not be approved, and both the second and third authors engaged in the discussion.

Three organisations active in the project area, the Institute of Conservation and Sustainable Development of the Amazon (IDESAM), the Getúlio Vargas Foundation (FGV,) and the Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF), expressed the view that the BR-319 reconstruction project shouldn’t be opposed and could move forward, provided Indigenous peoples were consulted and strong environmental conditions were included in the requirements for licensing.

Lessons of the past should not be forgotten. The situation parallels the history of the struggle against construction of Brazil’s Belo Monte Dam on the Xingu River in Pará state. Although most environmental NGOs vehemently opposed the dam project, some arrived in the dam area offering to help he displaced population gain better compensation and social programs, telling them that the dam project was inevitable and that they should not oppose to it.

Dom Erwin Kräutler, Bishop of the Xingu and a prominent dam opponent, pointed out the evident conflict of interest: the NGOs promoting better compensation for displaced people would have no reason to be present if the dam were not built and the population displaced. In the Belo Monte case, the dam company and the politicians promoting the dam were successful in provoking discord among the NGOs and among Indigenous leaders, contributing to the approval and execution of this notoriously disastrous project.

Indigenous rights in the Amazon

None of the Indigenous peoples impacted by the BR-319 project have been consulted, as required by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) Convention 169 (ILO, 1989) and by the Brazilian law that implements it.

Among the requirements is that this consultation must occur not only before the construction project itself, but also prior to the decision on whether to proceed with the project. Additionally, Indigenous peoples must have the right to reject the project.

Some interpretations of the convention soften this requirement to giving Indigenous peoples a “voice” in the decision-making process on projects that affect them, but not the power to veto those projects.

The transportation ministry’s plan has been to “consult” with only five Indigenous groups, even though the project would affect at least 68 groups. The plan has been to “consult” these groups while the highway construction is underway, with the task being done before the road’s official inauguration.

“Governance”

The BR-319 project has a long history of promoting highly unrealistic “governance” scenarios, including the first environmental impact assessment, which claimed the highway would resemble roads in Yellowstone National Park, where millions of tourists travel without leading to deforestation.

Similar scenarios persist, as demonstrated by the report of a working group composed of five departments of the National Department for Transport Infrastructure (DNIT). Unfortunately, history does not follow these scenarios, even when backed by major efforts from the government and civil society organisations, as demonstrated by the BR-163 (Santarém-Cuiabá) highway that the DNIT working group report uses as an example.

The NGOs that have adopted the position that including strong environmental conditions in the requirements for licensing would avoid an environmental and social disaster are providing de facto endorsement of official governance scenarios as a justification for allowing the project to go forward.

Members of the Brazilian federal police and army with whom we spoke to made clear that a scenario of future governance is fictitious, as the inspection bodies would lack the resources to monitor the area due to its size, complexity and danger. Organised crime already controls land grabbing and mining in the region, which has severely impacted traditional communities.

While neutrality was professed on the question of licensing and reconstructing the highway, in practice these organisations, especially IDESAM and FGV, were working to facilitate approval of the road. One example is the project by FGV titled “Promoting transparency and territorial governance in the context of installing highways in the Amazon – the case of BR-319”. As the title indicates, the project assumes the highway will be built. Indigenous leaders we consulted voiced strong opposition to the project, worried that any agreement could be misinterpreted by decision-makers as support for the construction, despite the communities’ resistance to the highway.

Another FGV document, titled “Territorial Development Agenda for the BR-319 Region: Strengthening Territories of Good Living,” seeks to promote territorial development in Vila Realidade, in the municipality of Humaitá. According to a report by the Federal Court of Accounts (TCU), this region’s sole economic activity is illegal deforestation. Illegal roads originating from Vila Realidade area are already encroaching on Indigenous territories, and it is unlikely that land grabbers and loggers will stop their activities, driven by the lure of quick and easy profits.

Indigenous leaders stated that representatives from FGV suggested it might be in their best interest to accept the proposed conditions since the BR-319 highway would be built regardless. They were advised that the most prudent approach would be to focus on mitigating the impacts on their territories by negotiating compensation with DNIT.

While some of these NGOs have expressed the desire to negotiate with all sides, attempting to establish governance between invaders and the invaded is impractical, as it would only intensify conflicts and heighten threats to traditional communities.

According to Indigenous leaders, the most severe violation of Indigenous peoples’ rights was committed by the International Institute for Education in Brazil (IEB). A document, which Indigenous leaders report was prepared by IEB and presented to them to sign, denounces a land invasion that is an urgent concern to the group, but it also includes a statement affirming approval of the BR-319 reconstruction project provided an extractive reserve is created to protect the Brazil nut groves used by the group. The leaders only became aware of the statement approving the road project after they had signed the document and followed IEB’s instructions to send it to the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA), Brazil’s National Indian Foundation (FUNAI) and DNIT.

We’ve omitted the names of the Indigenous leaders who made the denunciations, along with their ethnicities and communities, to guarantee their protection. All the complaints were made during the scientific event and leadership meeting held within the Federal University of Amazonas (UFAM), with the official presence of a representative of the Federal Public Ministry (MPF) and the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change (MMA).

The NGOs’ backing of the BR-319 project remained subtle until July 2024, when IDESAM withdrew from the Observatory of Climate and issued a statement to selected pro-BR-319 media and politicians. The trigger for this break was the judicial approval of the Observatory of Climate’s lawsuit challenging the BR-319 preliminary license, with IDESAM’s statement openly endorsing the highway’s reconstruction.

The federal attorney general’s office has filed an appeal to overturn the July 25th suspension of the preliminary license issued on July 25th. Unlike in the United States, Brazil’s attorney general lacks independence and typically advances the president’s political agenda.

The BR-319 project does not have an economic rationale, the motivation for the project being its value in electoral politics. The project’s benefit in winning votes in the state of Amazonas explains not only the support of local politicians, but also that of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

On 23 August, the First Regional Federal Court (TRF1) rejected the appeal. However, the attorney general’s office may continue to appeal, and future attempts could succeed due to Brazil’s “security suspension” laws. These laws, dating back to the military dictatorship of 1964, allow any decision to be overturned if deemed to cause “grave” harm to public economy, health, or order.

This legal mechanism has already been used to push the BR-319 project forward by reversing a judicial ruling that had paused the first public hearing, despite existing irregularities. Brazil’s legal system allows a seemingly endless series of appeals, enabling the attorney general’s office to continue appealing until it finds a sympathetic judge.

Motivations behind supporting BR-319

We have been trying to understand why some NGOs support the BR-319 reconstruction project, whether their support is overt or implicit. This has proven challenging due to the lack of transparency from both the organisations and their funders.

There is an extraordinary coincidence in that the NGOs that have refused to condemn the BR-319 project are all funded by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (GBMF).

Is it possible that GBMF has instructed the NGOs it supports to avoid opposing the BR-319 project? This might be done either explicitly by a clause in the grant contracts (which neither GBMF nor the NGOs have been willing to divulge) or by some sort of verbal admonishment. This is an open question.

GBMF was created by Intel co-founder Gordon Moore and his wife Betty Moore in 2000, with the aim of supporting scientific research and environmental conservation. GBMF’s grants to Brazilian institutions started in 2004 within the context of the Andes-Amazon Initiative.

The Foundation focuses its grants to Brazil in one area: land, terrestrial ecosystems, and land use. Their strategies for protected areas and Indigenous territories include conservation, consolidation, management, and monitoring. The area along the BR-319 highway is a particularly important part of GBMF’s funding.

GBMF has been providing funding for the desirable goal of promoting governance, but the NGO governance projects have a clear effect in facilitating approval of the BR-319 highway reconstruction project.

In response to a query about BR-319, the GBMF spokesperson shared the following statement with us:

The construction and pavement of roads in ecologically fragile regions may cause great destruction. We are not against roads; we are for establishing environmental and social safeguards that will protect nature and people.

In addition to the effect of the NGOs’ “governance” projects in facilitating approval of the license to permit construction, these projects and the implied continuation of funding for “governance” after the road is built is part of the dilemma that NGOs and their funders face with damaging development projects worldwide, namely the fact that the NGOs’ activities reduce the overall cost of the construction projects, thus making them more likely to be carried out.

The BR-319 project becomes much more appealing if the government only bears the cost of asphalt and other physical parts of the project, while international funders, including philanthropic organisations, foot the bill for governance measures, such as controlling deforestation and safeguarding Indigenous territories. In the case of BR-319, Brazil’s minister of transportation has stated that he wants to use money from the Amazon Fund to make the BR-319 project “viable”.

One unanswered question is whether GBMF could be funding the projects that facilitate approval of BR-319 to benefit the foundation’s own investments. An alignment between investments and the beneficiaries of the highway project does not necessarily mean that such a chain of influence exists.

Many foundations assign management of their assets either to a third-party company or to a department within the foundation that is separate from the grant-making activities. These arrangements commonly imply that the assets are managed to maximise profits without regard to the environmental and social impacts they cause. One cannot assume that the grant-making process of GBMF is influenced by the BR-319’s implications for the foundation’s investments. We would suggest, however, that this and other foundations in the environmental area should divest themselves from investments in environmentally damaging activities.

Oil and gas interests in BR-319

Oil and gas have been a significant part of GBMF’s investment portfolio, despite their global environmental impact and other concerns. The oil and gas sector would be a major beneficiary of the BR-319 highway and associated side roads.

GBMF’s investment portfolio does not include Rosneft, the Russian oil and gas giant that acquired the first 16 drilling concessions in the area to be accessed by the planned AM-366 highway branching off BR-319. However, GBMF has previously invested in SberBank, Russia’s largest investment bank, which finances Rosneft.

The expansive Solimões Sedimentary Area project for oil and gas extraction, located west of BR-319, offers significant investment opportunities for companies beyond Rosneft. The project covers a total area of 740,000 km² – larger than the US state of Texas.

GBMF has invested in various fossil fuel companies, including the Brazilian oil giant Petrobras, Russia’s LukOil – PJSC, the US-based Anadarko Petroleum, China Petroleum and Chemicals, the American firm Perusahaan Gas Comstock (which operates in Indonesia), India’s Petronet LNG, and TownGas China.

Brazil’s National Petroleum Agency (ANP) has designated nine large blocks of drilling rights along the BR-319 route. Although not in the highway’s “middle stretch”, they would benefit from the highway project. One of these blocks (AM-T-107) was bought by Eneva in partnership with ATEM in the December 2023 “end of the world auction”.

Eneva is a Brazilian gas and oil company that is highly recommended by Dynamo, which is GBMF’s asset management firm in Brazil. Dynamo itself holds a 10.06% stake in Eneva, and Eneva may merge with Vibra, a gas and oil company in which Dynamo holds a 10.28%.

Due to impact on Indigenous peoples, a judicial decision suspended signing drilling contracts for block AM-T-107 (plus four blocks bought by these companies in Amazonas, outside of the BR-319 area). Whether or not this suspension persists, the increased profitability that BR-319 would bring to the oil and gas sector in areas accessed from this highway and its side roads, would both stimulate fossil fuel extraction on a large scale and increase the chances of overcoming objections from impacted Indigenous peoples.

In addition to oil and gas, GBMF has invested in JBS, known as the “world’s largest animal protein company”. JBS’s slaughterhouses, along with the cattle ranches that supply them, are significant contributors to deforestation in the Amazon.

Large ranchers from the AMACRO deforestation hotspot, along with soy and other agribusiness interests, are planning to expand into the area west of BR-319, which would be opened by the planned AM-366 road, that also provides access to the oil and gas reserves.

Grants

IEB has received a total of 10 grants from GBMF, between 2004 and 2022, totalling over $14 million, including $2 million for work on BR-319. The objectives of the funding include “increasing the engagement” of Indigenous peoples in the middle section of BR-319 and increasing “public understanding” of “opportunities and gains for the sustainable development of the highway corridor”.

FGV has received funds from GBMF exceeding $6 million. The funding is “to develop parameters for the adoption of an approach based on human rights and aimed at preventing abuses and socio-environmental violations throughout the decision-making process for major works in Brazil, especially in the case of BR-319, in its entirety” and to conduct studies to promote the creation and implementation of a territorial governance plan along the BR-319 highway corridor in the Amazon.

IDESAM, an NGO headquartered in Manaus responsible for coordinating the BR-319 Observatory, received five grants from GBMF, between 2011 and 2023, totaling $2.4 million, over half of this ($1.24 million) being received in November 2023.

An IDESAM report, titled “Analysis of the Implementation of Conservation Units under the Influence of the BR-319 Highway”, in collaboration with FUNBIO (the Brazilian Biodiversity Fund), which is also funded by GBMF, outlined the benefits and opportunities that the reconstruction of BR-319 could offer to the Amazon region.

A Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation spokesperson shared the following statement:

The Moore foundation is supporting partners to avoid the ecological tipping point in the Amazon. To do this, it is necessary to have protected areas and Indigenous territories under effective management for conservation and sustainable use. There are many drivers of habitat change, one of the most important drivers is the development of infrastructure because it disturbs ecological connectivity and may establish social conditions that threaten local peoples’ livelihoods. The construction and pavement of roads in ecologically fragile regions may cause great destruction. We are not against roads; we are for establishing environmental and social safeguards that will protect nature and people.

The need for change

The proposed reconstruction of the BR-319 highway puts much of what remains of Brazil’s Amazon forest at risk and is surely one of the world’s environmentally damaging projects.

Environmental NGOs and philanthropic organisations should oppose projects that endanger biodiversity-rich areas. Moreover, these institutions need to embrace greater transparency and accountability, ensuring that their initiatives genuinely benefit the intended recipients: the environment and Indigenous communities.

Featured image via the Canary